Getting feedback from your audience and/or customers is honestly the most important feedback.

To get the most useful and eye-opening feedback, how you ask a question can be just as important as what you’re asking.

Whether you want to gauge client feedback on a new product, deploy regular NPS measurement, or test some messaging, you need to be sure that your survey instrument is useful and measuring what you think you are measuring.

There’s a ton of research that goes into understanding the ins and outs of survey psychology and the best ways to write survey questions. Some of it gets into hair-splitting territory, but today I’m sharing some of the most obvious mistakes I’ve seen in surveys.

What do I mean by mistake? Inviting response bias.

Your question wording makes it unlikely that all of your respondents are answering the same question. Or put differently, your question wording increases the likelihood that respondents are answering a question in a way other than you had intended and differently from other respondents.

This is a big issue for validity because you can’t really know what the respondents mean or what question they actually answered. This can ensure your data are useless and findings from your research cannot be used to make sound business decisions.

So let’s get into some common mistakes.

9 Common Survey Question Mistakes

TL;DR:

- Uncommon wording

- Complex question structure

- Double-barrel questions

- Behavioral questions without specified time period

- Scales with imbalanced anchors

- Scales with inconsistent anchoring concepts

- Response categories with gaps

- Response categories with overlaps

- Leading questions

1. Uncommon Wording

Make sure that your audience understands each word in your questionnaire. If you’re writing for an average audience, write at a sixth-grade level.

Don’t do this:

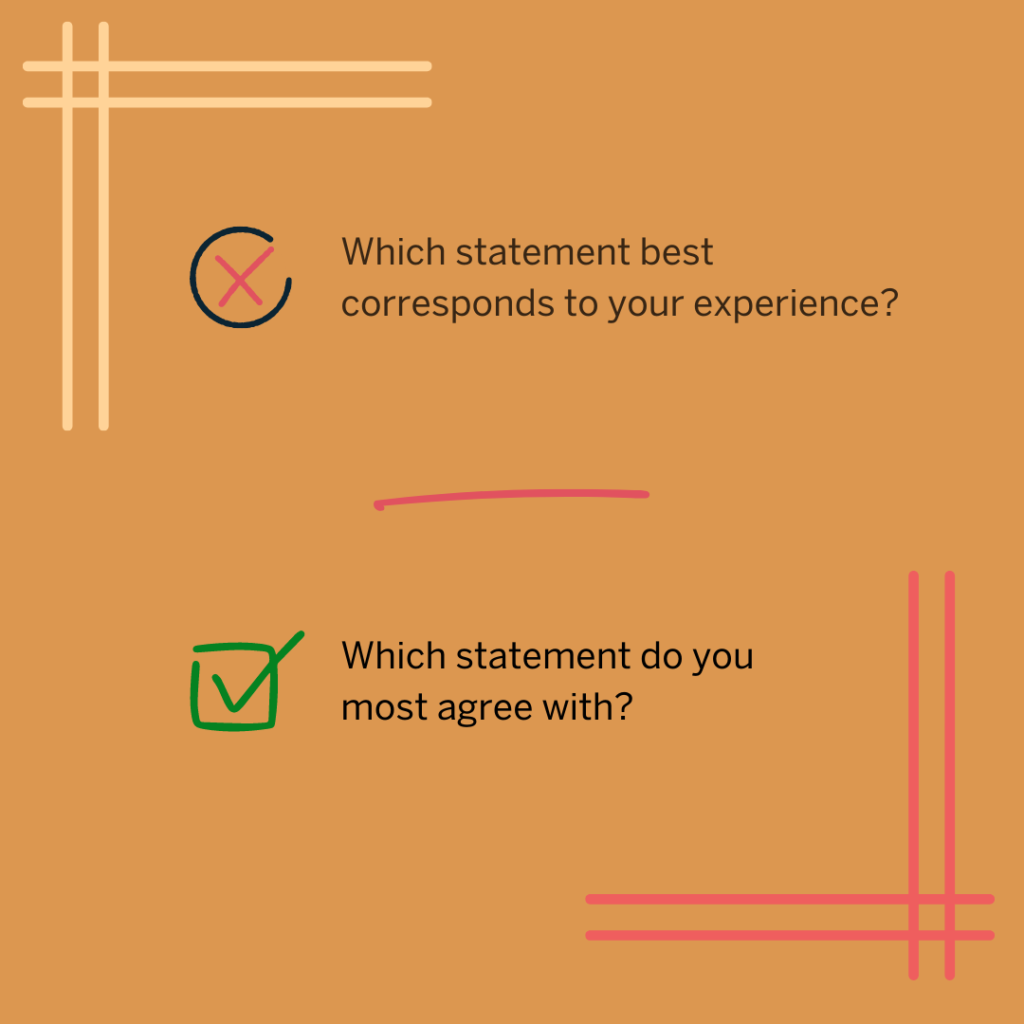

Which statement best corresponds to your experience?

Do this:

Which statement do you most agree with?

Why does this matter? You want to be sure that each of your respondents understand the question the same way so that they approach responding in the same way.

2. Complex question structure

Write your question as directly and concisely as possible:

- Avoid using too many clauses in a single sentence

- Use short sentences

- If you need to provide context, use a separate sentence prior to the question. Do not attempt to weave your context into the question.

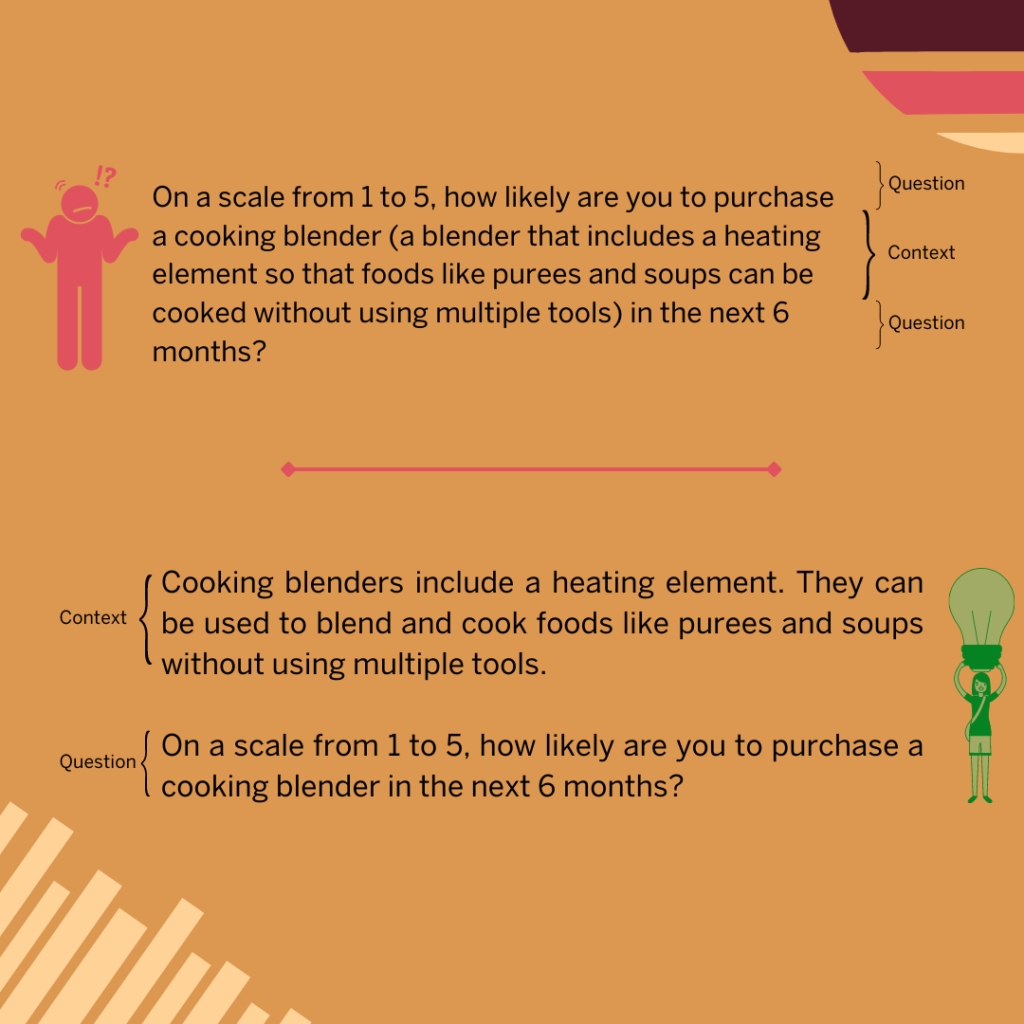

Don’t do this:

On a scale from 1 to 5, how likely are you to purchase a cooking blender (a blender that includes a heating element so that foods like purees and soups can be cooked without using multiple tools) in the next 6 months?

Do this:

Cooking blenders include a heating element. They can be used to blend and cook foods like purees and soups without using multiple tools.

On a scale from 1 to 5, how likely are you to purchase a cooking blender in the next 6 months?

Why does it matter? Confusing structure can not only cause respondents to lose track of what is actually being asked, but it can fatigue or frustrate them, which may increase your dropout rate (the proportion of respondents that did not complete your survey).

3. Double-barrel questions

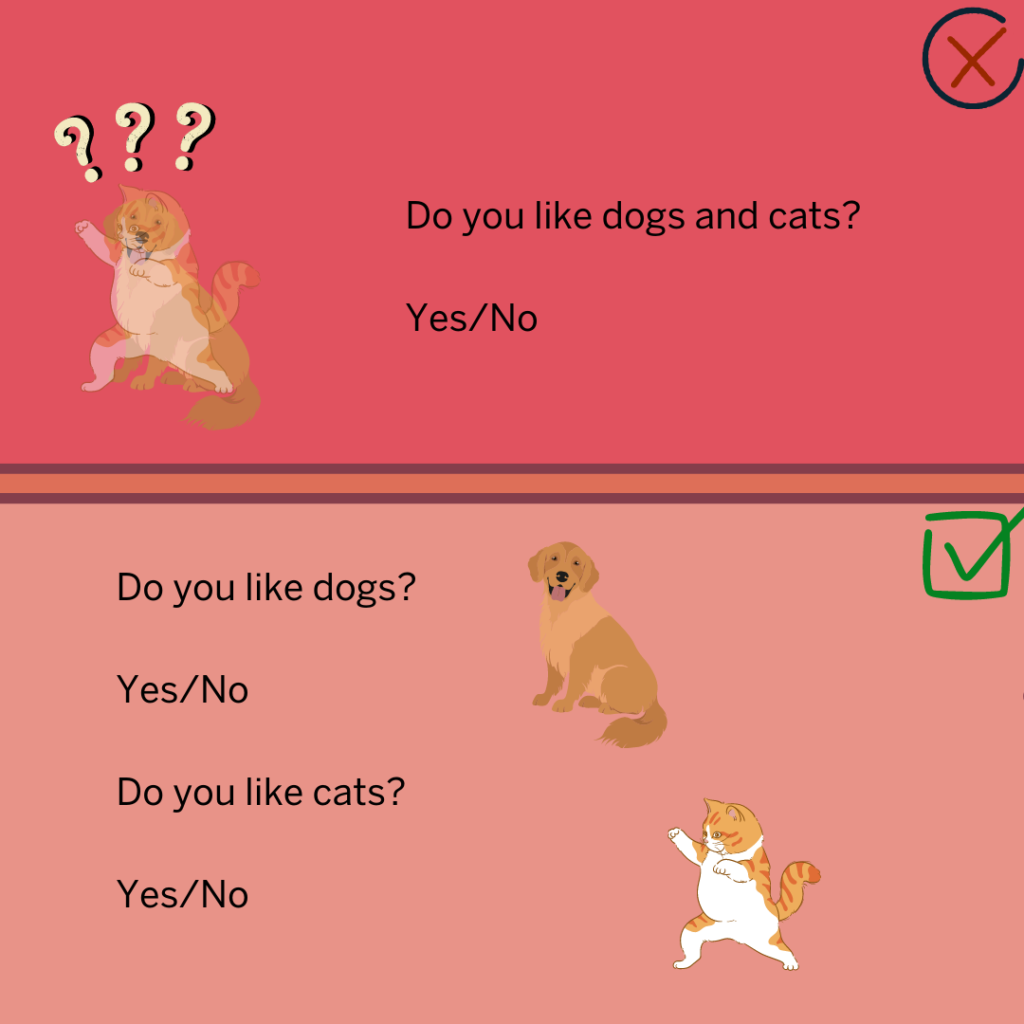

Double-barrel questions have more than one question within the same survey question. Don’t ask more than one question at a time. Respondents will not know which to answer. Plus, you won’t know which question they are responding to when analyzing your data.

Don’t do this:

Do you like dogs and cats?

Yes/No

Do this:

Do you like dogs?

Yes/No

Do you like cats?

Yes/No

Why does this matter? Because of the ambiguity, the double-barrel example gives six response options that you cannot track. Yes: (1) yes, I like dogs and cats, (2) yes, I like dogs but not cats, (3) yes, I like cats but not dogs. No: (4) no, I don’t like dogs or cats, (5) no, I don’t like dogs but I like cats, (6) no, I don’t like cats but like dogs. You will only know if respondents answered Yes or No, but will not be able to know to which option (animal) they are saying Yes or No to.

4. Behavioral questions without a specified time period

When you ask a question about behavior, you want to be sure to structure respondents’ thinking so that they can accurately recall. For example, self-reporting on behavior that has happened in the past 10 years is more difficult than self-reporting on the past month. There may be times in which longer durations of self-reporting are necessary, but make sure it is appropriate.

Don’t do this:

How often do you eat out for dinner instead of at home?

Do this:

In the past two weeks, how often have you purchased a meal at a restaurant?

If you want to know something about your respondents’ behaviors, you probably have a guiding reason.

It is unlikely that you will care about what they did 5, 10, or 15 years ago. You may care about what they’ve done in the past week, two weeks, or in recent months.

You may also want to compare behavior in different time periods. If you don’t specify a time period, your respondents will choose for you. There’s no way of knowing what period they are drawing upon to respond, so you will be getting answers to different questions from different respondents and comparing them begins to lose utility.

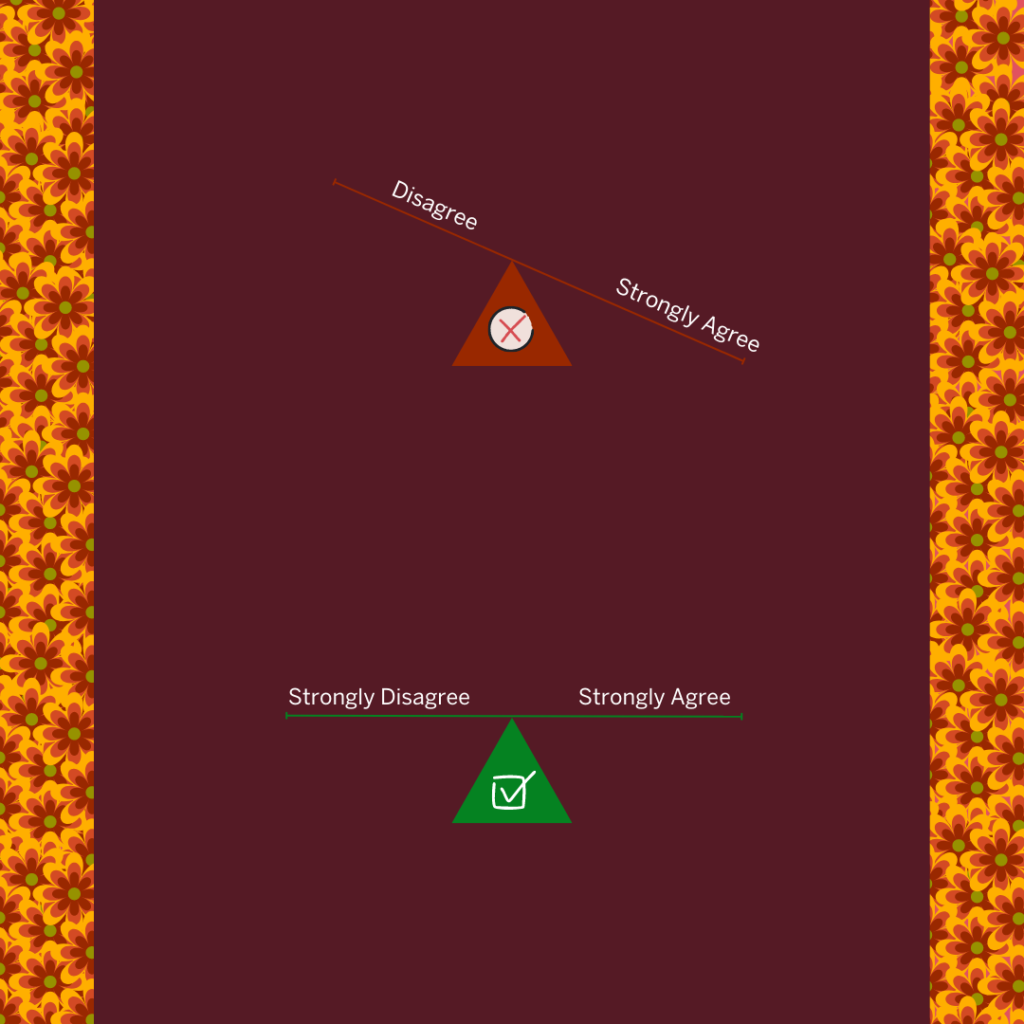

4. Bipolar scales with imbalanced anchors

When creating a bipolar scale question, make sure your endpoints are of equivalent magnitude in the opposite directions. For example, your lowest point (not at all) should be the mirror opposite of the highest scale point (all the time). You’ll also want to be sure to label the scale to make it easier for respondents to conceptualize their responses.

Don’t do this:

Disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree

Do this:

Strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree

If you want to measure the magnitude of respondent sentiments (such as agreement), you need to include the entire range that those sentiments can take. If you don’t you lose the capacity to assess the degree to which a respondent feels that sentiment. That is a huge loss. There’s a big difference between liking aspects of your services and loving them.

6. Scales with inconsistent anchoring concepts

When creating a scale question, make sure that you don’t include different concepts. It may sound silly, but we have seen questions that include different anchor concepts such as disagree/true rather than disagree/agree.

Don’t do this:

Strongly oppose, oppose, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree

Do this:

Strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree

This one is pretty self-explanatory. Make it easy for your respondents by having consistent ideas on a scale.

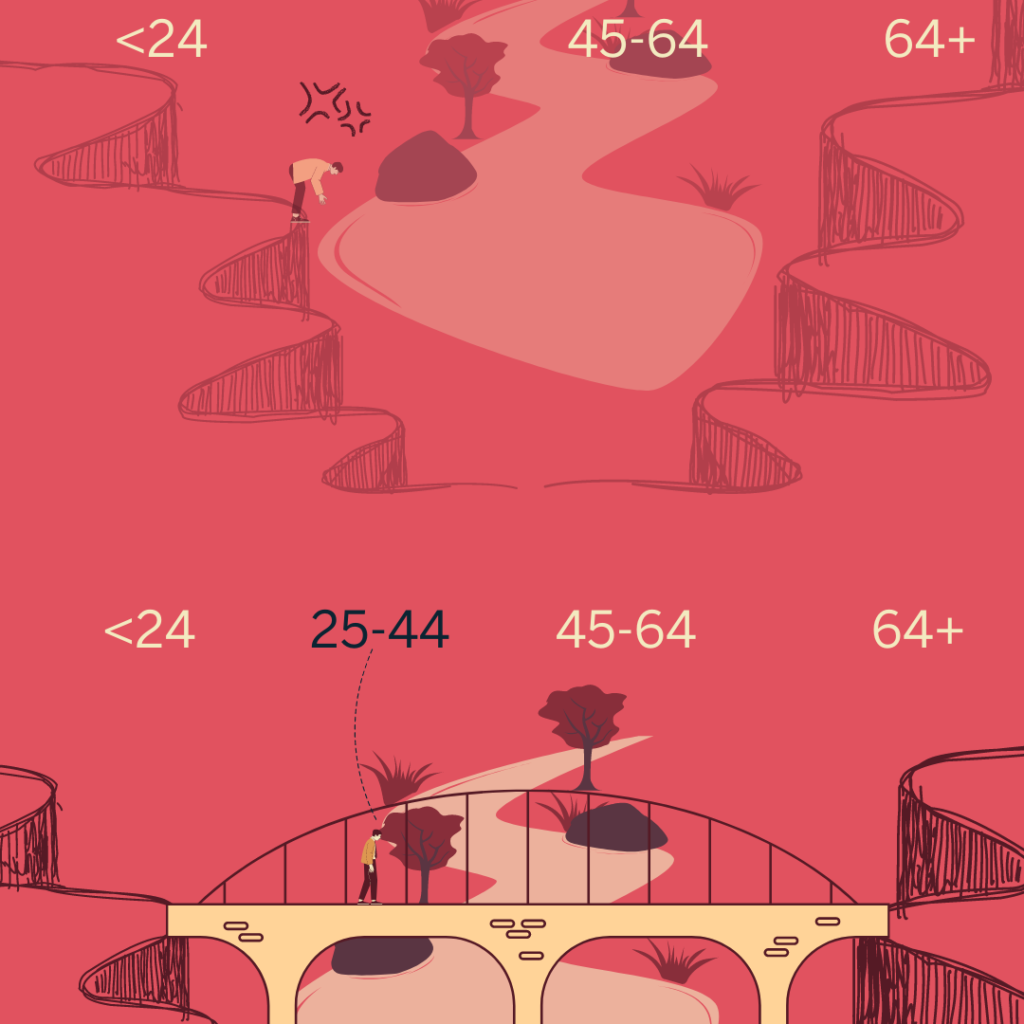

7. Response categories with gaps

It goes without saying that any value a response can take should be accounted for in your response categories. For example, you wouldn’t ask about someone’s household income and start the categories at $100,000.

Don’t do this:

What is your age?

24 or younger, 25-34, 35-44, 55-64, 65 or older

Do this:

What is your age?24 or younger, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65 or older

Again, pretty self-explanatory, but omitting an entire category does happen. Don’t do it. Anyone the missing response applies to will not be able to answer accurately.

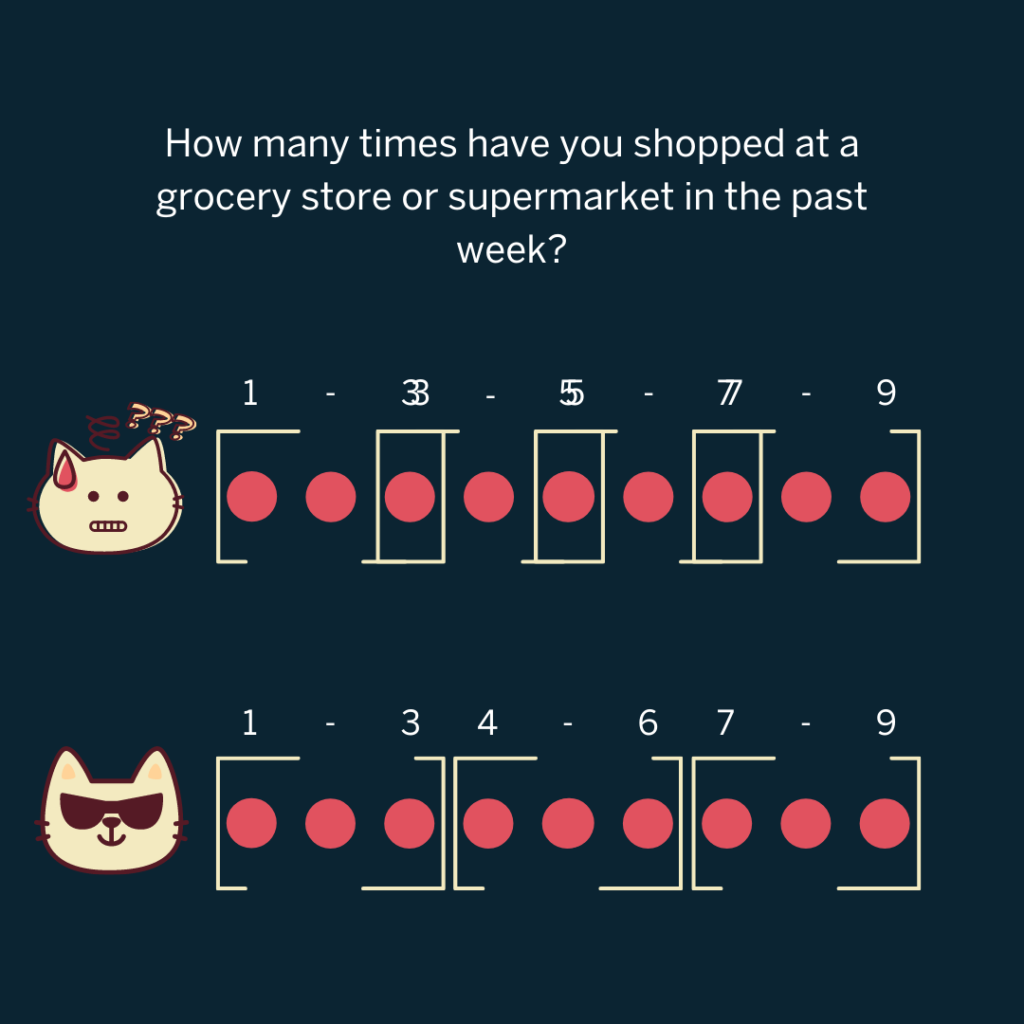

8. Response categories with overlaps

If you have categorical questions, make sure each response option is distinct and that there is no overlap between categories.

Don’t do this:

How many times have you shopped at a grocery store or supermarket in the past week?

1-3, 3-5, 5-7, 7 or more

Do this:

How many times have you shopped at a grocery store or supermarket in the past week?

1-3, 4-6, 7-9, 9 or more

If different response categories contain the same value, then either response category is equally valid. For example, either 1-3 or 3-5 would be correct if a respondent shopped 3 times in the past week.

3, 5, and 7 fall into two categories. Let’s say you are asking a question about years of professional experience, there is a big difference between 1-3 and 3-5 years. But if you have overlap in the categories, you may end up with responses showing less or more experience that your respondents actually have.

9. Leading questions

Don’t include an answer in your question. This will influence respondents to answer in a manner that is consistent with the question wording but that isn’t consistent with their experience.

Don’t do this:

How great was reading this blog?

Do this:

From did not enjoy to enjoy, how much did you enjoy reading this blog?

This one is powerful. For example, leading questions can manufacture memories in interrogation subjects. You don’t want your question to tell respondents what precisely their response should be. If you do this, you’ll get inaccurate responses.

Wrap up

When creating questionnaires, it’s imperative to write questions in ways that solicit responses that are consistent with what we intend to measure and such that all respondents understand the questions the same way.

Avoid these common mistakes:

- Uncommon wording

- Complex question structure

- Double-barrel questions

- Behavioral questions without specified time period

- Scales with imbalanced anchors

- Scales with inconsistent anchoring concepts

- Response categories with gaps

- Response categories with overlaps

- Leading questions

Want help designing a survey? Schedule a call with us